Low-dimensional representations of MD simulations

Autoencoders, a type of neural network that learns how to optimally compress information, share some superficial resemblances to collective variables (CVs) used in MD simulations.

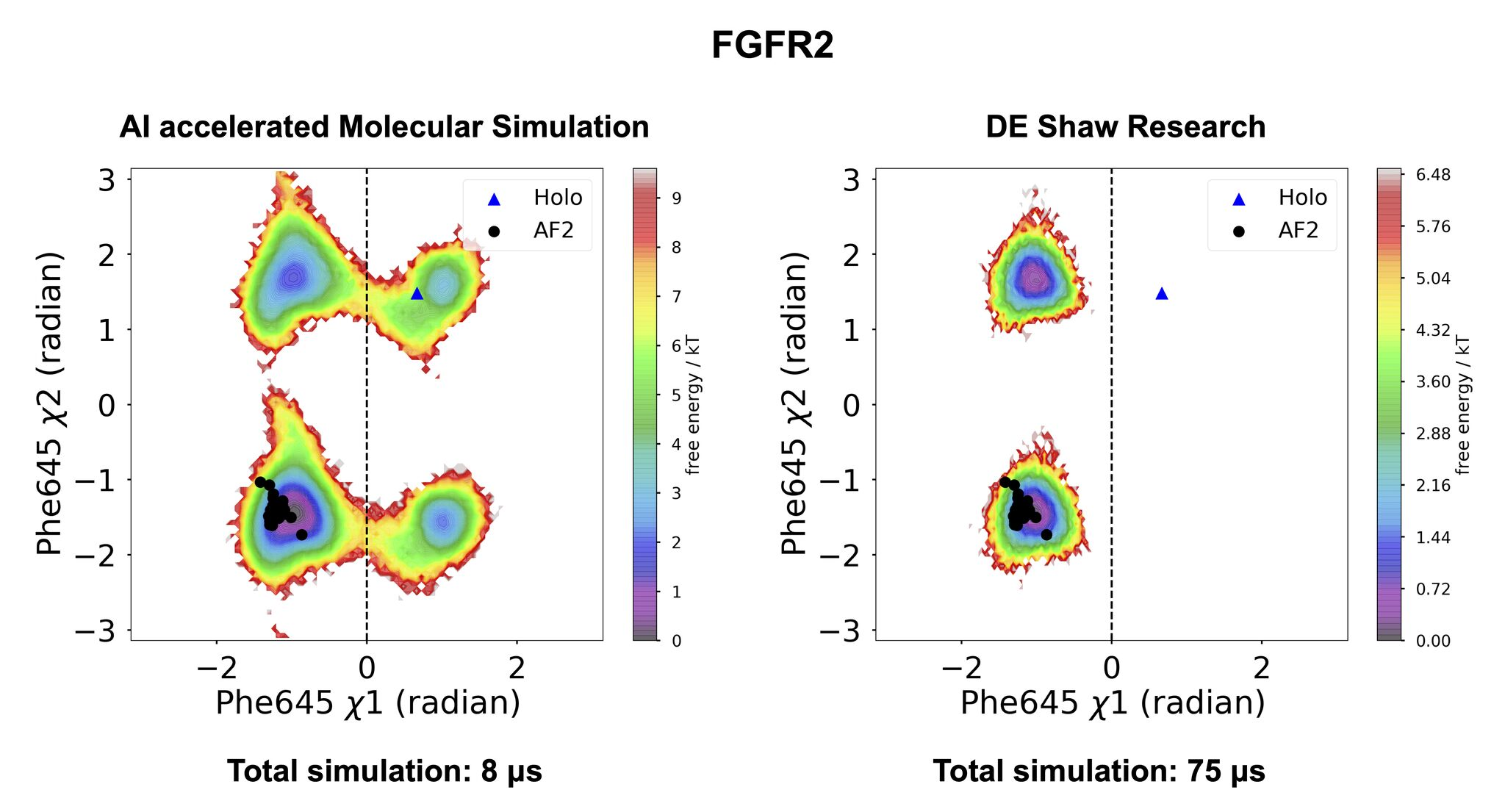

In the latter case, though, humans usually have to hunt for informative movements, and then get ignore everything else. High-quality CVs reduce high-dimensional processes being simulated to just a few features, such as backbone or side chain torsion angles or distances, placing the focus on the system’s propensity to sample different substates as a function of such features. This improves interpretability at the cost of comprehensiveness. Here’s an example from a recent paper on acceleration of MD simulations [1]:

Figure from [1]

Figure from [1]

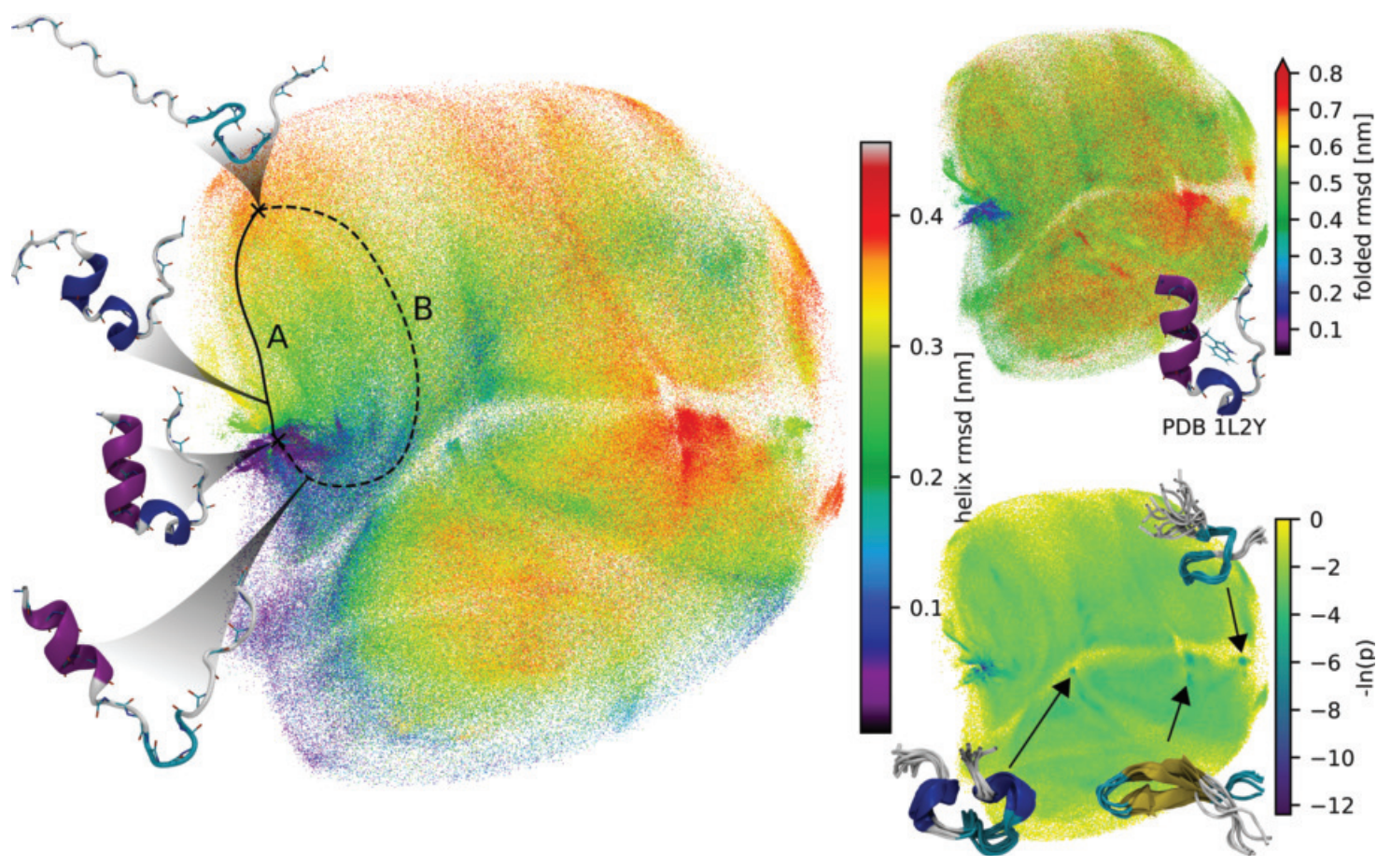

Now contrast that with autoencoders, which have the advantage of compressing far more information to a low-dimensional representation (termed the latent space), without necessarily needing to be human-interpretable.

Figure from [2]

Figure from [2]

In the context of MD, autoencoders are nothing new: they’ve been used to learn simplified representations of more complex, generally nonlinear systems [2-4]. In one example from the Baker group, the protein folding neural network RosettaFold was fine-tuned with a 256-dimension autoencoder exclusively on the protein Ras [5]. The method worked, in that it successfully sampled conformations unseen during training from this latent space, but at the cost of being uninterpretable given its huge latent space.

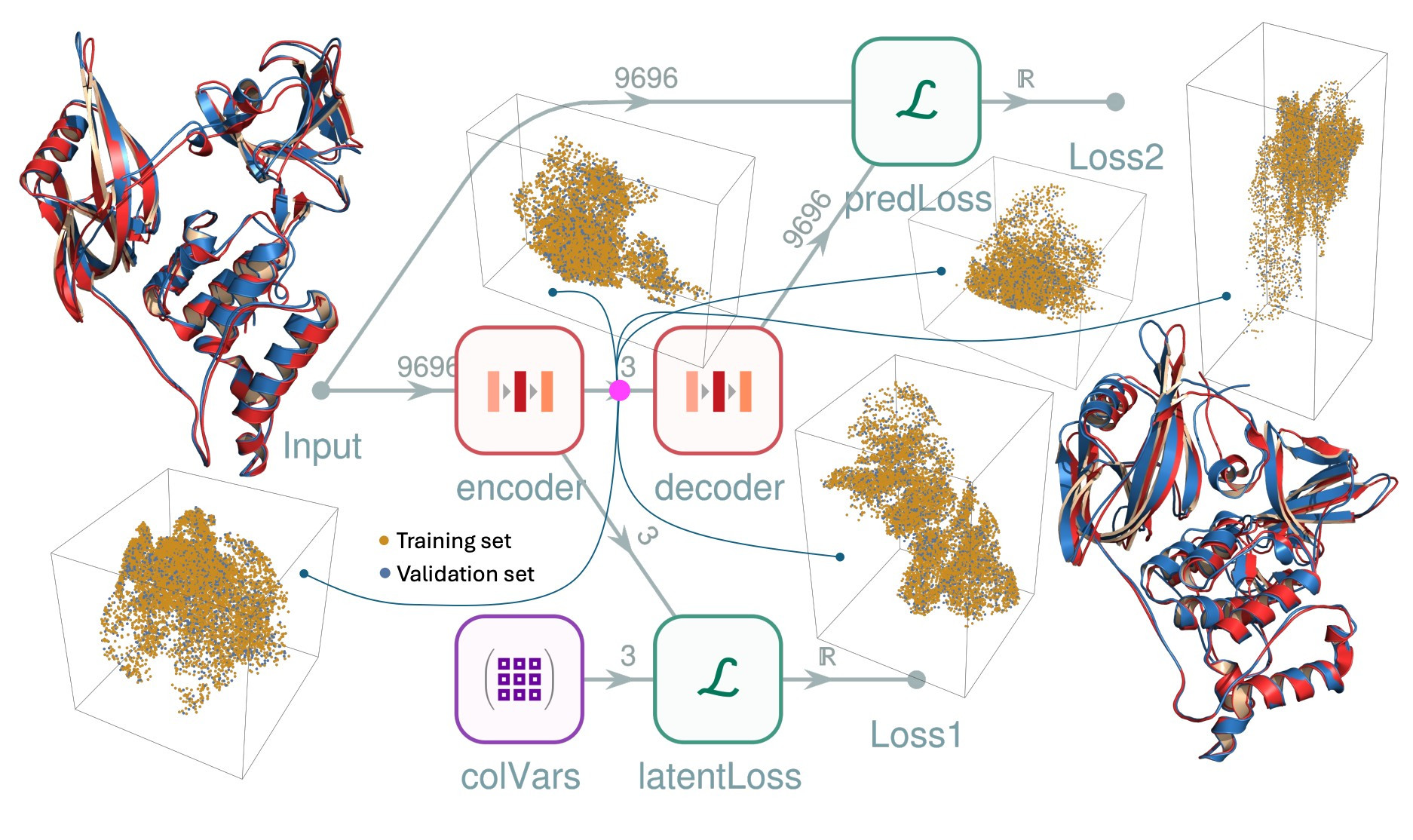

I haven’t found an example that attempts to directly link the comprehensiveness of an autoencoder’s latent representation to the interpretability of human-identified CVs until last week [6]. In that preprint by authors Kolossváry & Coffey, an autoencoder was trained to both recover structure and organize its latent space to match human-picked CVs. This allowed the authors to both visualize the protein’s free energy landscape and generate putative transition paths from the autoencoder’s latent space. In practice, the approach reconstructed CRBN’s conformational change to an impressive accuracy of 1.6 angstroms RMSD (compared to 1.2 angstroms when the link with hand-picked CVs was excluded).

Figure from [6]

Figure from [6]

Interestingly, this architecture, despite being presented in a paper mentioning protein folding neural networks like AlphaFold2 and RosettaFold, doesn’t seem to incorporate any of their advancements. For instance, the challenge of rotational and translational invariance, which was solved by the former using their structure module [7], the latter using an SE(3)-transformer [8], and ignored altogether by AlphaFold3 and its derivatives [9], gets lazily addressed by learning exclusively from poses that have been aligned to a common reference frame. They also use RMSD loss, rather than FAPE loss which has been shown to permit more stable training on biomolecular structures [10].

None of the three applications that I envisioned for such a tool are discussed. First, the authors focus solely on CRBN, and do not mention the emergence of cryptic pockets that often trigger the use of MD in the first place. Second, only the wildtype system is simulated; the method could be useful in comparing how well a missense mutation retains or disrupts a protein’s dynamics. Third, there is no evidence to suggest that the global latent space at all reflects the transition dynamics in complex systems, such as fold-switching proteins. So although I’m excited about the method, probably we need to see more before judging its extensibility and whether it can be further improved.

This post was prepared with the help of Gemini 2.0 Flash

- Schönherr et al. “Discovery of lirafugratinib (RLY-4008), a highly selective irreversible small-molecule inhibitor of FGFR2” PNAS 2024

- Lemke & Peter “EncoderMap: Dimensionality reduction and generation of molecule conformations” JCTC 2019

- Wehmeyer & Noé “Time-lagged autoencoders: Deep learning of slow collective variables for molecular kinetics” J Chem Phys 2018

- Vani et al. “Exploring kinase asp-phe-gly (DFG) loop conformational stability with AlphaFold2-RAVE” JCIM 2023

- Mansoor et al. “Protein ensemble generation through variational autoencoder latent space sampling” JCTC 2024

- Kolossváry & Coffey “Reinforced molecular dynamics: Physics-infused generative machine learning model explores CRBN activation process” biorxiv 2025

- Jumper et al. “Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold” Nature 2021

- Baek et al. “Accurate prediction of protein structures and interactions using a three-track neural network” Science 2021

- Abramson et al. “Accurate structure prediction of biomolecular interactions with AlphaFold 3” Nature 2024

- Baek et al. “Efficient and accurate prediction of protein structure using RoseTTAFold2” biorxiv 2023