Training data for conformational flexibility prediction

How much data from molecular dynamics simulations are needed to predict protein flexibility?

The loadedness of the term “protein dynamics” complicates many attempts at figuring out what scientists want exactly when using modern AI/ML tools to predict protein structural heterogeneity. For the two to three years when AlphaFold2 and related methods were the state of the art, modeling dynamics mostly meant hacking these methods to yield some conformational heterogeneity1. In the last year and a half or so, however, several high-quality neural networks have been released that tackle this problem more directly, at various levels of comprehensiveness: AlphaFlow2, BioEmu3, and Str2str4 being some examples.

It’s worth backing up to get a sense of the breadth of this topic. Usually the term “dynamics” is meant to invoke A) the range of a protein’s motion, with some states sampled more than others, B) the relative frequency at which different sample those minima (Boltzmann weights), C) their interconversion pathways and sampling frequencies, D) the modulating effects of ligands, including well-placed water molecules or hydrogen atoms via side chain protonation, and E) how each of these properties can be further modified by specific mutations, particularly those implicated in disease. For several decades, well-designed molecular dynamics simulations have been able to interrogate these problems, albeit excrutiatingly slowly. So machine learning, particularly neural networks adapted from structure prediction, have naturally emerged as computational shortcuts for learning those aspects about proteins. The challenge is that there doesn’t appear to be any evidence that those neural networks learn much about protein structure beyond the low-energy states evident from coevolutionary data5, despite some claims otherwise6.

In general it seems that two types of neural networks have emerged to fill this gap. The first learns from simulation data for individual proteins and attempts to, in effect, learn fundamental properties about those systems by interpolating them (example here). The second try to be more generalist, and learn from huge quantities of structural and MD data.

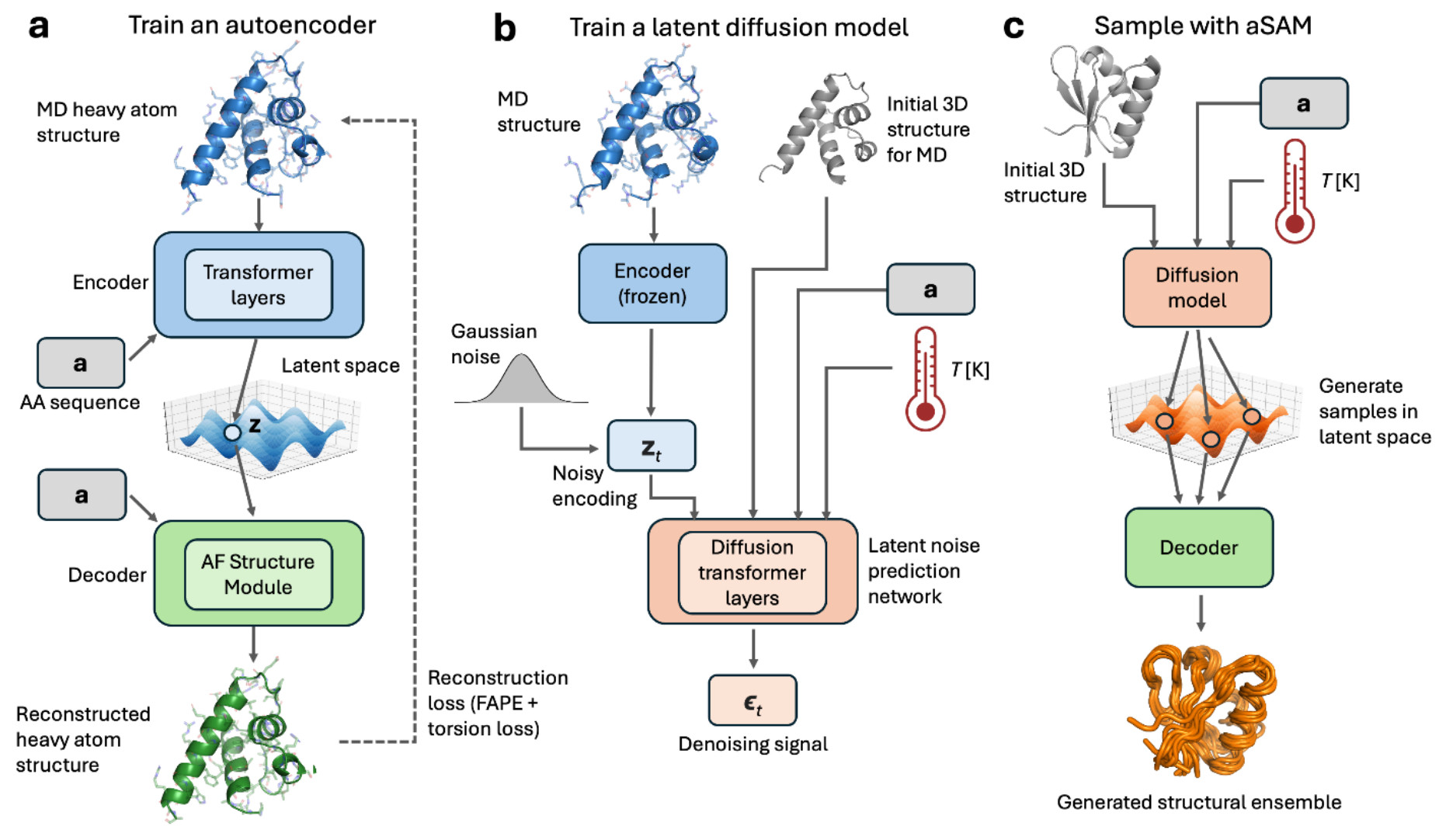

Earlier this week a preprint was released that attempts to do the second 7. The method, sAMt, uses a variational autoencoder and an input structure as a template to model proteins heterogeneity from sequence alone.

There are many things to like about this preprint - unlike the method I discussed before, it uses more modern neural network architectures such as the AlphaFold structure module8 and diffusion models, as well as the frame aligned point error loss function. But one thing stood out in this document that warrants further discussion:

“…free energy values from aSAMt were not in accurate quantitative agreement with the long MD results indicating that aSAMt learned the extent of conformational sampling covering a broad range of conformations but struggles in correctly reproducing relative probabilities between different states . This result may be expected, since the training data from mdCATH were simulations at most 500 ns long with few transitions between alternate states at a given temperature from which relative probabilities could have been learned…”

In contrast, the long MD simulations against which the conformers are compared last one or more milliseconds9. That’s approximately 2,000 longer than the training examples. Moreover, the modeled proteins were explicitly chosen for their ability to quickly fold and unfold, suggesting a degree of comprehensiveness in the simulations. In contrast, the proteins in mdCATH are simply short simulations of a cross-section of structural diversity10.

This point has been raised in the past in verbal discussions on AlphaFlow. The motions captured in mdCATH are, in effect, Brownian motion, which is neither difficult nor interesting to predict. The value added by a neural network capable of predicting certain properties of protein dynamics would come from, at a minimum, a capacity to predict the weighted distribution of different conformations. Thus far, BioEmu is the closest to achieving this, although its accurate predictions are limited to conformational breadth and folded versus unfolded states. That said, there’s no reason that further progress in this field will unlock this capability to learn from the short MD simulations we have available.

-

Sala et al “Modeling conformational states of proteins with AlphaFold” Curr Opin Struct Biol 2023 ↩

-

Lewis et al “Scalable emulation of protein equilibrium ensembles with generative deep learning” biorxiv 2024 ↩

-

Jing et al “AlphaFold Meets Flow Matching for Generating Protein Ensembles” ICML 2024 ↩

-

Lu et al “Str2Str: A Score-based Framework for Zero-shot Protein Conformation Sampling” ICLR 2024 ↩

-

Vani et al “Exploring Kinase Asp-Phe-Gly (DFG) Loop Conformational Stability with AlphaFold2-RAVE” JCIM 2023 ↩

-

de Silva et al “High-throughput prediction of protein conformational distributions with subsampled AlphaFold2” Nature Comms 2024 ↩

-

Janson et al “Deep generative modeling of temperature-dependent structural ensembles of proteins” biorxiv 2025 ↩

-

Jumper et al “Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold” Nature 2021 ↩

-

Lindorff-Larson et al “How fast-folding proteins fold” Science 2011 ↩

-

Mirarchi et al “mdCATH: A Large-Scale MD Dataset for Data-Driven Computational Biophysics” Scientific Data 2024 ↩